By Wan Yew Fai, CA (Singapore), CPA (Australia), B. Acc (Singapore)

In matrimonial cases, it is not uncommon that one spouse will hide assets from the other spouse, especially when the marriage is on the rocks. If this were a corporate or commercial case, that would likely have been classified as “cheating” and be deemed a criminal act.

Between a husband and wife however, the recourse for the party being deprived of these hidden assets is adverse inference.

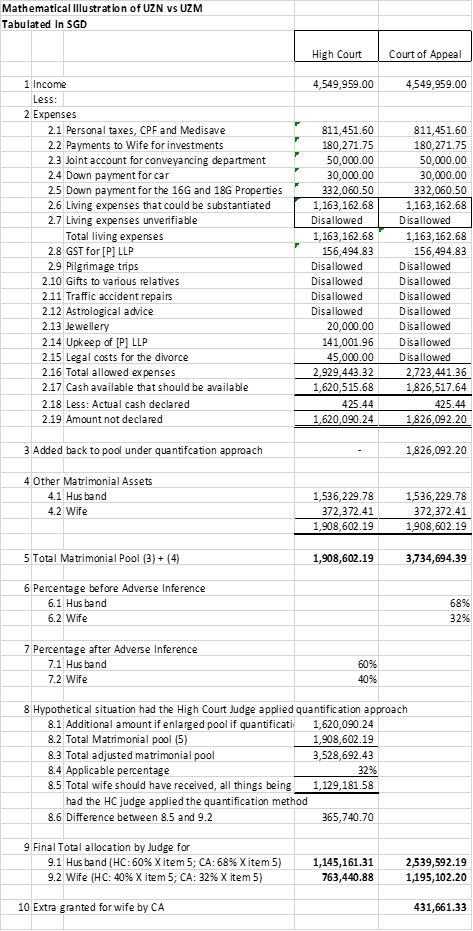

In this article, I will share my analysis of how the High Court and subsequently the Court of Appeal applied adverse inference in the case of UZN v UZM [1]. I will also demonstrate how the quantitative method may be a more equitable method than the uplift method.

Using income and expenditure to establish the extent of marital assets

Instead of just listing down all the assets of both husband and wife, the parties used the unusual method of income less expenditure to establish the extent of their marital assets. The Court of Appeal stated that this method should not be used as a matter of course but may be used in cases where there is already good reason to suspect, upon a preliminary overview, that there is a mismatch between a party’s assets and their means. [2]

How then was it used?

In a nutshell, the accounting expert’s analysis showed that the Husband’s income from 2000 to 2016 was $4.55 mil against which his expenditures were $4.12 mil. Of the $4.12 mil expenses, also over the same period, the Husband claimed that his living expenses alone were $2.045 mil. Deducting the income from the expenditure, the expert opined that the cash balance should have been at least $0.43mil. However, the Husband said he only had $500 left. Expert also added that he could only substantiate $1.16 mil out of the alleged $2.045 mil living expenses, leaving a sum of $0.885 mil that he could not verify.

Range of opinion and expert’s duties

In this case, the parties and the High Court Judge were content to rely on the expert’s analysis to determine whether the Husband had any assets which he had failed to disclose.[3] The conclusion was that the cash balance should be $0.43 mil instead of a mere $500.

Is this however really the case? In my view, it may be more equitable to go a few steps further.

First, the expert should have given an opinion on the range of the Husband’s cash balance.

According to Order 40A Rule 3(e) of the Rules of Court, “An expert report must, where there is a range of opinion on the matters dealt with in the report, summarise the range of opinion and give reasons for this opinion.”

So, in this particular case, the range from the expert’s analysis could have been as follows:

- Lower end: $0.43 mil cash that the Husband should at least have; to

- Higher end: $1.315 mil (i.e. $0.43 mil plus the $0.885 mil living expenses that he could not verify).

2nd, the expert should have gone into some details relating to each bigger ticket expense item to assist the court.

Instead, the High Court Judge had to go through line by line in the expense listing to make a determination about the amount that should be included in the matrimonial pool without any further guidance and analysis from the expert.

I therefore believe it is also the duty of the expert to state the reasons for the range of values and then shed some further light on each of the individual expense items with respect to the nature of these expenses in order to assist in how the expenses should be classified. From the classification, one can then conclude whether they should be part of the matrimonial pool.

At the High Court, certain expenses were in fact added back into the matrimonial pool. Examples of these expenses are the amounts spent on pilgrimage trips, gifts to various relatives, traffic accident repairs, legal costs and astrological advise.

The High Court Judge also drew adverse inference against the Husband and applied the uplift method by increasing the Wife’s share by another 8% up. The Wife was awarded 40% instead of 32% with the uplift method. The Wife appealed the decision on concerns whether the Judge was correct to have given effect to the adverse inference in this manner, as well as the true extent to which the Husband has failed to disclose his assets.

Classification of various reasons for undervaluation

The Court of Appeal gave the following 4 reasons that result in an undervaluation of the matrimonial pool.

- Inadvertence

- Concealment (e.g., arising due to intentional non-disclosure),

- Wrongful dissipation (e.g., falling under s 132 of the Women’s Charter) or

- Innocent dissipation

Techniques used to deal with adverse inference

The Court of Appeal also provides two methods that the court may use to deal with adverse inference:

a) Quantification Approach – “The court may make a finding on the value of the undisclosed assets based on the available evidence… and include that value in the matrimonial pool for division.”

b) Uplift Approach – “The court may order a higher proportion of the known assets to be given to the other party.”

In my 20 odd years’ experience as a forensic accountant, most if not all of my matrimonial cases dealt with substantial sums being dissipated or concealed. I dare say if someone bothers to take steps to keep assets undisclosed and out of reach of the other spouse, we are usually dealing with significant amounts. I will not be surprised if the undisclosed amount averages 4 times the disclosed amount. Needless to say, this is not always the same for every case and it can go higher or lower.

If the amount stashed away is way larger, then a better and more equitable approach, I surmise, will be the quantitative approach.

To illustrate, we use a case where a judge orders that the matrimonial asset to be divided 50:50 for a disclosed pool of $1 mil. For the uplift approach, unless the Judge gives the extreme uplift of 100% (which I don’t believe will happen) by adding another 50% to the injured spouse, the resulting award will only yield that party $1mil.

Now, if we apply my analysis that non-disclosed assets can amount to 4 times of disclosed assets, then what we are talking about will be $4 mil undisclosed assets not subject to any application of any percentage. It is clear that the quantitative approach of adding the undisclosed asset and then applying 50% (half of $5 mil =$2.5 mil) will mean more financially for the injured spouse.

In the case of UZN v UZM, the wife got S$763,440.88 with the uplift approach in the High Court. The quantification approach was not used. Had it been used, her entitlement would have been S$1,129,181.58. That’s a substantial increase of S$365,740.70. In fact, at the Court of Appeal, because of the quantitative approach adopted and additional expense items that the CA disallowed and added back into the matrimonial pool, the wife got even more at $1,195,102.20.

Below is a table I have created to illustrate the computation:

Wan Yew Fai is a Certified Public Accountant with a special focus on forensic accounting in matrimonial matters. He started his career in forensic accounting in 1992 but his forensic training really began when he was Asia-Pacific Regional Auditor for US Government USAID program. Yew Fai has been appointed an expert witness in various litigation cases, mainly in matrimonial matters but also in shareholders’ disputes including that of family businesses. Over the past 20 odd years, he has also been engaged as a case consultant with numerous law firms. In the course of his engagements. Yew Fai has provided Court-approved valuations of multiple businesses. Yew Fai’s experience in the commercial world includes that of managing his own construction business for 15 years. Yew Fai is a sought after trainer and has lectured in financial institutions of higher learning.

____________________________

[1] UZN v UZM [2020] SGCA 109; UZM v UZN [2019] SGHCF 26

[2] Ibid, para 25

[3] Ibid, para 5