Third Party’s Interest In Matrimonial Assets: The Case of UDA v UDB

Can the Family Justice Courts (FJC) divide a property in another’s name as if it is a matrimonial asset in a divorce?

On 24 April 2018, 5 of our Apex Court’s judges sat in the case of UDA v UDB and another to make the ruling that is to determine proceedings relating to ownership disputes over third parties’ interests in alleged matrimonial assets and/or properties.

There are two situations in particular:

- Where a spouse holds an asset in his name, but claims to be holding it on trust for a third party, whilst the other spouse disputes this (“Situation 1”); and

- Where the asset is in the name of a third party, but one or both spouses claim that it is a matrimonial asset because the third party is holding the whole or part of the property on trust for one or both spouses (“Situation 2”).

UDA v UDB and another, illustrates Situation 2. A 10-year legal battle between the divorcing parties culminated in the hotly contested dispute relating to a property held in the name of the wife and her mother. The husband claimed that the mother was holding it on trust for him and his wife as he had paid a very substantial portion of the purchase price. The mother denied these assertions.

The main issue was therefore whether the FJC can decide claims by a third party on the ownership of a disputed asset and make orders that would directly affect the third party’s interest in the disputed asset. A related issue was whether the FJC could then take spouses’ beneficial interests in disputed assets into account in ordering the division of matrimonial assets.

Our Court of Appeal says “no” to the 1st question and a limited “yes” to the 2nd.

In the past, when faced with Situations 1 and 2, the FJC has made its own determinations on whether to treat the contested asset as part of the matrimonial pool.

Since the landmark ruling in UDA v UDB, it is now clear that the FJC, whether operating in the Family Division or as a Family Court, has no powers to hear claims by third parties.

With only one exception, it is now required that a civil suit be started to determine the issue of ownership of the asset, with the third party as a party to the suit. Only if the court in the civil suit declares the property to be beneficially owned by one of the spouses in the divorce suit can the asset be included as part of the matrimonial pool.

The exception is if the divorcing spouses agree that the court is to determine whether the asset is a matrimonial asset without involving the third party’s participation at all or making an order directly affecting the property.

Determining the issue of ownership

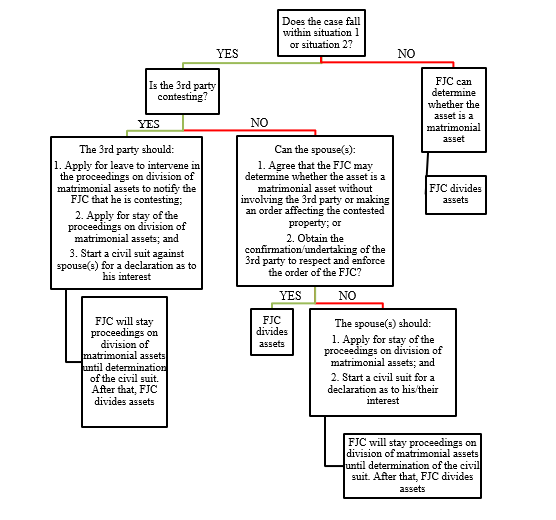

The following flowchart illustrates the effect of the ruling.

In coming to the decision, the court began with an analysis of s 112 of the Women’s Charter. They concluded that an item of property that is legally and beneficially owned by a third party is not covered by s 112(1) and the court’s power under that section does not extend to it.

Following that, they reasoned that if the FJC treats the disputed asset as a matrimonial asset and makes adjustments in the division of other assets to account for its value, the spouse who has had to account to the other for the value of the asset might ultimately be prejudiced.

This is because the determination of the ownership of the disputed property in the FJC proceedings will not bind the third party; it may be determined later on that the third party was both the legal and beneficial owner of the asset. In such a situation, the spouse that has already accounted to the other for the asset will find himself having to account to the third party for the asset.

The court therefore agreed with the lower court that the ancillary matters should be stayed to allow the husband to pursue a civil action to determine the disputed property interests.

Writer’s Note

This CA case is especially timely now as we increasingly see cases where title and legal ownership seem hopelessly entangled, involving multiple business interests, joint investments and complex portfolios of shares and stocks.

However, this ruling also means the expenditure of substantial resources and prolonged divorce proceedings for parties to pursue a separate civil suit.

It is of course in the best interests of all that they adopt the collaborative approaches encouraged by the FJC or engage in conciliatory dispute resolution methods like mediation to see if agreements can be sought.

Yet, increasingly spouses are tempted to engage in more manipulation of the matrimonial pool by cleverly maneuvering assets under the names of third parties out of reach of the other spouse.

What, then, can be done to limit the success of such dishonest tactics?

Forensic Accounting and Investigations

A practical starting point from a cost-benefit angle will be to engage forensic accountants and investigators to perform a preliminary assessment to determine firstly if we have enough evidence to support proof of ownership and secondly, on the value of the asset that can be potentially added into the matrimonial pool. Such evidence includes tracing the monies to procure the asset; the benefits enjoyed by the party or his behaviour supporting claims of existence and ownership.

The costs of a preliminary assessment will be a fraction of the costs of a separate suit, and the result of that assessment helps to determine whether the civil suit is worth pursuing. It will also assist in mediation or a neutral evaluation of the party’s case.

If indeed a civil suit is inevitable, the forensic accountant can also provide an independent opinion on whether the asset should be included in the pool.

As a family lawyer, I often work closely with accountants especially where businesses are involved. I believe that this multidisciplinary approach allows my clients to properly assess their options, make informed decisions and ultimately achieve a fair division of their matrimonial assets.

This article is written by Susan Tay with kind contributions and assistance from Ms Shirley Tay and Ms Isabel Chew-Lau.